Language Technologies FOR ALL

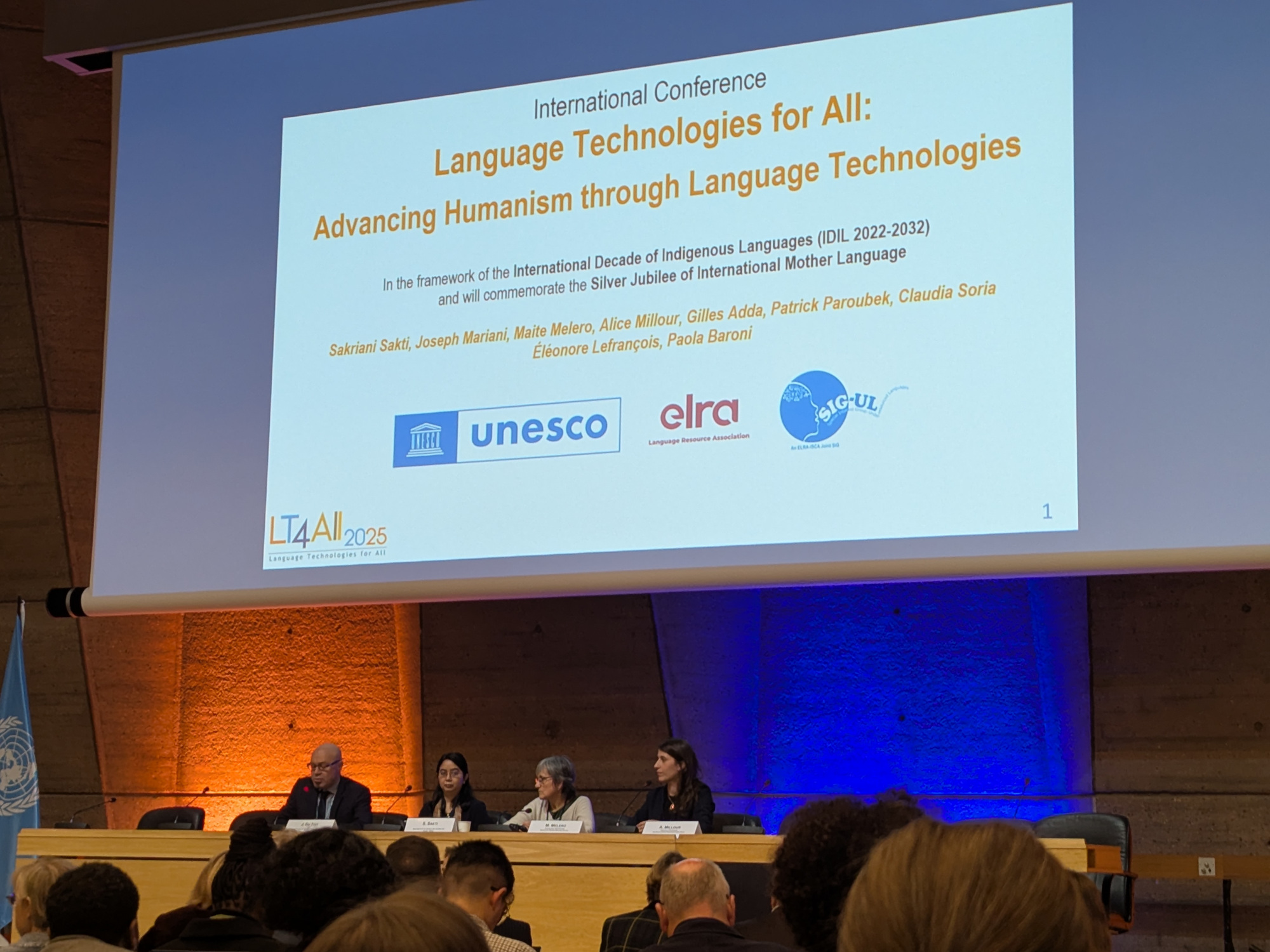

Imagine for a moment, waking up one morning to discover that your language could not be used on any of your devices. Your phone and tablet do not display your language. None of your devices allow you to type in your language. If you have a smart speaker, it no longer responds to your language. At best, you can record and send an audio message in your communications app of choice (whose interface is no longer in your own language), but the automatic transcription feature no longer works for your language. This was the question posed by one of the speakers at the UNESCO Language Technologies for All Conference that I attended last week. Sit with this for a moment and reflect on what that would feel like.

Although digital devices work just fine for a few hundred of the world’s most populous languages, the situation this speaker asked us to imagine is the daily experience for more than a billion people, who speak one of the thousands of languages for which digital tools—even “simple” tools like keyboards, dictionaries, and spell checkers, not to mention more complex tools like large language models or automated speech recognition systems—do not yet exist.

To be sure, for many of these people, digital devices and even access to the Internet are likely unavailable, as well. However, if our goal is to bring the positive benefits of digital platforms and communication tools to all people, then making those tools function in the languages that those people prefer is an important part of that task.

This is a complex problem. One part of the solution involves assembling corpora of digital data in these languages. This is not an easy task, and it raises questions like, who should have the right to manage this kind of language data? Some language communities have taken intentional action to change the trajectory of their language’s digital footprint. At this conference, the NaijaVoices project introduced their concept of “data farming” (an intentional contrast with “data mining”) for languages of Nigeria as an example of a community-based solution to this problem.

The trajectory of a language’s digital footprint is also related to issues of language preservation and revitalization. At this conference, we also heard examples of the successful work that has been done by the Estonian and Icelandic language communities, to develop language technologies that aim to promote the use of these languages in digital contexts.

There remains much work to be done, but I’m excited to be among those who are working for equitable approaches that promote the well-being of communities, regardless of the languages that they prefer to use!

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: